Mabel Elsworth Todd

The educational approach now known as “Ideokinesis” emerged in the early 1900s, a turbulent period of extraordinary creativity in the performing arts and physical culture. The start of the new century generated a progressive intellectual climate in which scholars questioned Cartesian conceptions of mind/body separation and began to explore alternative views. Mabel Elsworth Todd took part in these developments after a long and arduous process of self-healing.

Mabel was the second child born into a prominent Syracuse, New York family. An early childhood illness weakened her kidneys so severely that the doctors prepared the family for the possibility of lifelong invalidism. Fortunately, Mabel grew strong enough to enter a private school for girls and fully engage in her elementary and secondary education. At the Keble School, she developed a keen interest in science, which was unusual for a girl in those times. An exceptional relationship with her science teacher provided opportunities for special projects and encouraged her passion for the subject.

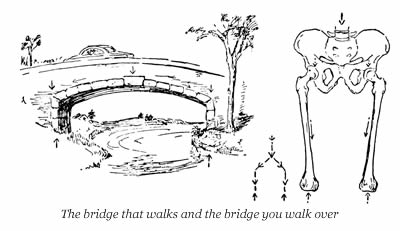

As a teenager, Mabel sustained a severe back injury in a terrible fall from which it was feared she might never recover. Regular osteopathy treatments were helpful, but she struggled with pain and debilitating weakness until she began taking charge of her own recovery. The foundation of her self-directed rehabilitation was her high school physics study. In an avid investigation of anatomy and kinesiology books, she found ways of applying rudimentary mechanics to the workings of the human musculoskeletal system. That information became the basis for Mabel’s efforts to strengthen her body, regain her balance and restore her confidence in movement.

Todd’s fall and self-directed recovery delayed her pursuit of higher education for several years. When she finally enrolled in the Emerson College of Oratory in Boston at the age of 26, she was eager to explore their courses in movement and the use of the voice. Todd became fascinated by the incidence of vocal difficulties and concurrent problems with posture and basic coordination. When Todd and a few colleagues began teaching in Boston at the start of World War I, she added techniques discovered in her own rehabilitation to the methods she learned through the study of oratory.

In 1914, Todd set up a private teaching studio for her approach in Boston near Emerson College. In addition to her clientele of oratory students, prominent society matrons frequented Mabel Todd’s studio when their work in makeshift factories supporting the war effort took a physical toll. Todd’s lessons helped them recover and learn to use their bodies more efficiently. Several Boston orthopedists were very impressed by the results of Todd’s techniques and sent their patients to her studio for lessons.

Todd’s longtime pupils became assistant teachers as her clientele grew. Often with backgrounds in physical education or nursing, almost all of Todd’s studio teachers suffered from serious health challenges that her work relieved and gradually improved. Although they incorporated their individual backgrounds into her techniques, Todd’s training of the studio teachers brought further order and clarity to her teaching method.

Todd’s approach was conducted in private lessons that centered around a procedure she called the “table work.” The teacher began by showing a feature of the musculoskeletal system to explain an aspect of ideal body balance. She concluded the discussion by suggesting an image as a metaphor for the alignment concept. Then, the pupil reclined on a padded table and pictured the image as the teacher provided precise information on its location and the direction of its action through touch. The teacher encouraged the pupil to merely picture the image without directing the body to produce a muscular response. The new image and imagery introduced previously were also practiced while resting in various positions and performing basic movements like rolling, crawling, or walking. Finally, the pupil was encouraged to review the imagery while resting or engaging in simple movements between lessons.

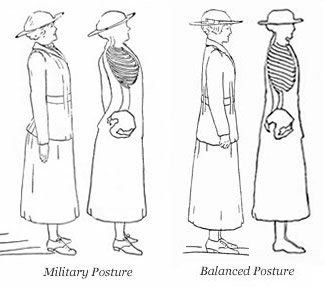

Encouraged by the orthopedists who were impressed with her work, Todd began writing about her approach during this period. Her first articles, written for the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, explained her new “Principles of Posture.” Much of this writing described the nature of ideal alignment from a mechanical standpoint in contrast to the popular conceptions of posture that military training practices or women’s fashion trends encouraged. Todd also explained how “thinking” of goals in the form of mental images could be used to break poor habits and establish better postural patterns.

Encouraged by the orthopedists who were impressed with her work, Todd began writing about her approach during this period. Her first articles, written for the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, explained her new “Principles of Posture.” Much of this writing described the nature of ideal alignment from a mechanical standpoint in contrast to the popular conceptions of posture that military training practices or women’s fashion trends encouraged. Todd also explained how “thinking” of goals in the form of mental images could be used to break poor habits and establish better postural patterns.

Around 1920, Todd established a second studio in New York City, where her lessons attracted pupils from theater, dance, opera, music and professional sports. Todd also made her work known in physical education departments in nearby colleges and universities. She became particularly interested in the bachelor’s degree program offered by the Department of Physical Education of the Teachers College, Columbia University. Dr. Jesse Feiring Williams, the head of the department at the time, was spearheading a new approach to physical education that challenged the dualistic paradigm separating persons into two parts: a material body and an immaterial mind. His landmark text, Principles of Physical Education, promoted physical education as a “laboratory” for learning all the subject areas as well as enhancing social responsibility and moral values.

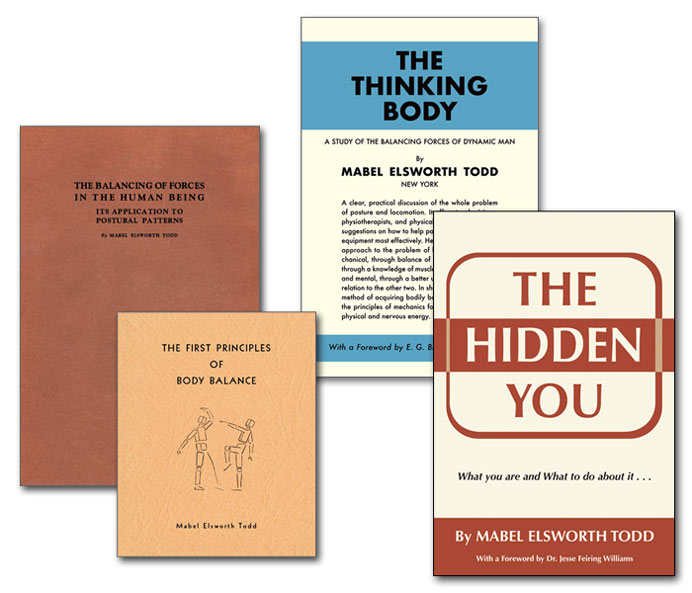

Todd’s approach to “natural posture” fit nicely into Williams’ vision of a new form of “education through the physical.” The Teachers College physical education curriculum included hygiene, natural dancing, applied anatomy and physiology, play and playgrounds, individual sports, rhythmic gymnastics, body mechanics and posture as integral components. After she graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 1927, Williams hired Todd as a lecturer to teach a course on her method. During that period, Todd wrote The Balancing of Forces in the Human Being: Its Application to Postural Patterns as a syllabus for her students.

After Todd resigned from the faculty of Columbia University in 1931. She lectured for another year at the New School for Social Research and then limited her teaching to expand her syllabus into a book. Published in 1937, The Thinking Body: A Study of the Balancing Forces of Dynamic Man, promoted an understanding of body alignment as a function of mechanical principles. Although substantive from a kinesiological standpoint, the work was also rich with examples of human body engineering simplified into imagery. The process by which sustained concentration upon images could effect change in habits of posture and movement was a central theme.

The publication of The Thinking Body brought a new wave of recognition for Todd’s ideas that sustained her teaching studios through the early 1940s. But gradually, her formerly supportive medical colleagues faded from prominence. The new generation of leadership was less interested and sometimes quite critical of Todd’s teaching procedures. At one point, a group of physicians in New York City threatened a lawsuit against her studio business. Lacking the energy and funding to mount a legal defense, Todd agreed to close her New York studio in an out-of-court settlement.

The publication of The Thinking Body brought a new wave of recognition for Todd’s ideas that sustained her teaching studios through the early 1940s. But gradually, her formerly supportive medical colleagues faded from prominence. The new generation of leadership was less interested and sometimes quite critical of Todd’s teaching procedures. At one point, a group of physicians in New York City threatened a lawsuit against her studio business. Lacking the energy and funding to mount a legal defense, Todd agreed to close her New York studio in an out-of-court settlement.

In the early 1950s, Todd left the east coast for California after being advised that a milder climate might ease her ongoing health problems. Todd established a small teaching studio in the Los Angeles area, cultivated a small upscale Hollywood clientele and continued to work on her writing. Her second book, The Hidden You, was written during this period.

The new text expanded upon themes she discussed in The Thinking Body and suggested psychological and spiritual implications of her approach to posture and movement. For Todd, it was only reasonable that the sensitive exploration of body balance would inform all dimensions of one’s being. Soon after The Hidden You was published in 1953, Todd suffered a series of heart attacks; she died in California three years later. Todd’s remaining studio teachers gradually lost contact with each other. Fortunately, two of Todd’s most dedicated protégés, Barbara Clark and Lulu Sweigard, developed unique and substantive interpretations of her approach, which advanced her work into the second half of the 20th century.

— Pamela Matt (Revised 2024)

The writings of Mabel Todd can be purchased at https://tbi-media.org.

Bibliography for Mabel Elsworth Todd

Brunnström, S. “The Changing Conception of Posture: Methods of Dealing with Faulty Posture,” The Physiotherapy Review 20 (2): 79-84,1940. Traces concepts of proper posture originating with the “standing at attention” approach prescribed in Swedish Gymnastics; explains the biomechanical futility of common postural admonitions; gives high praise to Todd and Sweigard’s innovative teaching methods.

Corefield, L. “Shelf Life: The Thinking Body: The Legacy of Mabel Todd Explained – Preview of a Video,” Contact Quarterly 25(1): 8-9, Spring/Summer 2000.

Matt, P. A Kinesthetic Legacy: The Life and Works of Barbara Clark. Tempe, AZ: TBI Media 2020. Although primarily a biography of Barbara Clark, one of Todd’s students, this work contains historical background on Mabel Elsworth Todd. https://tbi-media.org/product/a-kinesthetic-legacy/

Rolland, J. “Mabel Todd: An Introduction to her Work,” Contact Quarterly 5(1) Fall 1979: 6-7.

Todd, M. “Principles of Posture,” The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 182 (26): 645-649, June 24, 1920. This “first paper” of Mabel Todd presents her description of the nature of normal posture and discusses methods of posture correction.

——— “Principles of Posture, with Special Reference to the Mechanics of the Hip Joint,” The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 184 (25): 667-673, June 23, 1921. Todd continues her discussion of body mechanics in this “second paper” with emphasis upon the balance and interdependence of various units of weight in the body and the significance of normal mechanics of the hip joint.

——— The Balancing of Forces in the Human Being: Its Application to Postural Patterns. New York, NY: Columbia University Teachers College. May 1, 1929. Reprint by Thinking Body Institute Media, 2017. Class syllabus with focus on the rationale and goals of Todd’s method of posture education; her “procedure for thinking,” in contrast to the use of remedial exercise, is explained. https://tbi-media.org/product/balancing-of-forces/.

——— “Our Strains and Tensions,” Progressive Education 7: 242-6, 1931. Briefly introduces Todd’s approach to achieving mechanical balance in the body as a means of relief from the stresses of modern life.

——– “Basic Principles Underlying Posture,” Journal of Health and Physical Education (2) 8: 13-15, 56-57, 1931. Written as an introduction to her approach when Todd was a lecturer at Columbia University.

———The Thinking Body: A Study of the Balancing Forces of Dynamic Man (1937). Reprint by Thinking Body Institute Media, 2021. Todd’s classic work explains the kinesiological basis for her approach to posture correction. https://tbi-media.org/product/the-thinking-body/.

——— The Hidden You: What You Are and What to Do About It (1953). Reprint by Thinking Body Institute Media, 2019. Todd’s last and most controversial work. https://tbi-media.org/product/the-hidden-you/.

(c) 2023 The Thinking Body Institute. All rights reserved. Reprint with permission only.