Lulu E. Sweigard

Lulu Edith Sweigard was born in Sharpsburg, Iowa, on April 19, 1895. A year after graduating from high school in 1913, she began working on her Physical Education Diploma at Iowa State Teachers College; college records indicate she was an outstanding scholar and student leader. As a teaching assistant, Sweigard worked closely with faculty and was encouraged to continue her studies beyond the requirements for the teaching diploma to earn the Bachelor of Arts degree in Physical Education. Her work impressed the college authorities, and she joined the faculty as an instructor upon graduating in 1918. A few years later, she was promoted to assistant professor. In 1926 she was awarded a leave of absence to pursue graduate studies in physical education at the Teachers College, Columbia University.

During her leave at the Teachers College, Sweigard met Mabel Todd, who was teaching the course “Basic Principles of Posture.” Todd’s view that posture and body mechanics could be improved by thinking of imagery was a radical departure from anything Sweigard had previously learned. In a talk delivered at a bi-national dance conference in 1971, she explained,

My background of formal education was in the field of physical education where I was well indoctrinated with the idea that exercises for various parts of the body were the means of improving (correcting?) body alignment, the supposition obviously being that poor posture is due to weakness of some of the muscles.

Studying with Mabel Todd changed Sweigard’s views and radically altered the direction of her academic career. She could see that Todd’s approach produced better body alignment with greater ease than traditional exercise teaching. But she was also aware that scientific proof of its effectiveness would be required for the physical education establishment to even begin to consider the merits of Todd’s approach. Acknowledging that Todd’s command of kinesiology provided sound scientific support for many of her ideas, Sweigard looked to developments in neurophysiology for a better understanding of how concentration on imagery could facilitate postural change. She also recognized that Todd’s approach needed organization and simplification to be successful as a posture correction system for physical education. Thus, rather than returning to Iowa after completing her master’s degree in 1927, Sweigard remained in New York and dedicated herself to resolving the issues inspired by her exposure to Todd’s teaching. Although research, analysis and objectivity were essential to the task, Sweigard was also quite idealistic. In her preface to the 1972 reprint of The Thinking Body, she explained:

Two years of study with Miss Todd convinced me that . . . any teaching which could produce such unquestionably good results in body alignment with simultaneous increase in efficiency and ease should be available to all in the educational system and not be confined to private teaching.

Between 1929 and 1931, Sweigard conducted a research study that was intended to validate Todd’s approach by documenting specific changes in skeletal relationships that occurred through her teaching procedures. The research involved 200 adult female students ranging in age from twenty to fifty years who received Todd’s posture training in thirty-minute classes for fifteen weeks. Before and after the training period, Sweigard used a device called a Posturimeter to measure the changes in their skeletal alignment.

Sweigard found that Todd’s teaching method of thinking rather than doing produced measurable changes in the relative position of skeletal parts and that the changes were consistent. A few of the improvements Sweigard noted were an increase in overall height in both the sitting and standing positions, a decrease in the width and circumference of the rib cage and an increase in the length of the spine. Reviewing the findings provided a clear picture of the most widespread postural faults and demonstrated how bodies could change toward greater conformity with the principles of mechanics.

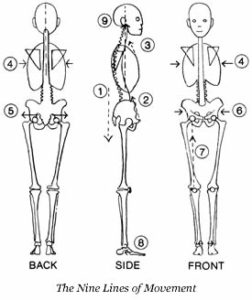

Unfortunately, Sweigard’s study was not published due to the lack of a control group, questions about the reliability of surface measurements and the need for statistical data analysis. Although Sweigard was disappointed that her study did not have the impact on physical education that she anticipated, the research was invaluable from many other perspectives. Studying and then summarizing the changes in alignment that she observed, Sweigard began to standardize a simpler version of Todd’s educational method that emphasized the following postural changes:

The Nine Lines-of-Movement

The Nine Lines-of-Movement

1. Lengthen the spine downward.

2. Shorten distance between mid front pelvis and 12th thoracic vertebra.

3. From top of the sternum to top of the spine.

4. Narrow the rib case.

5. Widen the back of the pelvis.

6. Narrow the front of the pelvis.

7. From center of knee to center of femoral joint.

8. From big toe to heel.

9. Lengthen the central axis of the trunk upward.

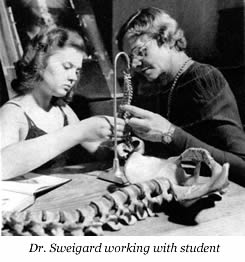

Sweigard became an instructor for the School of Education at New York University in 1931 and began working on her doctorate. During that period, she continued to refine her teaching method and embarked on a very ambitious research project. Dr. Jay B. Nash, the head of the department at the time, was instrumental in securing financial support from the General Electric Corporation to X-ray five hundred subjects in the standing position that she carefully analyzed. Sweigard’s doctoral thesis titled “Bilateral Asymmetry in the Alignment of the Human Body” presented her analysis of the X-rays and other measurements and concluded that deviations in skeletal symmetry were consistent and predictive of differences in both the stability and range of motion of the legs. Since 400 of the 500 subjects were also in her posture classes at NYU, the study also furthered the development of Sweigard’s tactile expertise. Comparing differences in muscle tone to the skeletal x-rays of the students, Sweigard developed the “educated hands” that she considered an indispensable aid in teaching an approach she began to call “Neuromuscular Reeducation.”

After completing her doctoral thesis in 1939, articles about Sweigard’s work appeared in the New York Times and Life Magazine. An article in the Physiotherapy Review explained the futility of common postural admonitions, like “pinch the buttocks” or “squeeze the shoulder blades,” and praised Todd and Sweigard’s innovative teaching. Sweigard was invited to participate in a Symposium on Posture that assembled all the acknowledged experts in the field and resulted in a major publication. Still, all the attention to Sweigard’s new ideas failed to change entrenched posture correction practices in physical education. Except for a few of her NYU doctoral students, most physical education teachers continued using traditional exercise curatives for poor posture.

In the 1940s and 50s, physical education’s interest in posture and body mechanics gradually waned. Fortunately, the dance world began taking notice of Sweigard’s teaching. Mabel Todd’s New York City studio had already exposed a few dancers to thinking their way toward improved body alignment. Others became interested in Todd’s ideas by reading The Thinking Body. When Todd closed her studio in New York, many dancers sought Sweigard’s assistance when medical treatment for their injuries was unsuccessful. Sweigard could see that their poor neuromuscular habits caused muscular imbalances that could not withstand the new dance training practices.

Word of the effectiveness of Sweigard’s approach spread rapidly, and the number of dancers wanting lessons soon became overwhelming. To separate those who were serious about pursuing neuromuscular reeducation from those who were seeking a quick fix for their problems, Sweigard often required prospective students to study human anatomy as a preparation for their private lessons with her. After evaluating the unique difficulties of each dancer and tailoring a program to meet those needs, she sometimes enlisted help from Todd’s former assistant teachers to keep pace with the demand. Those dancers who persisted in their studies with Sweigard learned that her work was a means for optimizing the coordination of the body and distinctly advantageous to anyone seriously pursuing the art of dance. Once beyond the intimidation almost all of them felt as they encountered the depth and breadth of Sweigard’s knowledge, her students embodied the lessons of neuromuscular reeducation in their dancing and began experimenting with various ways of applying their new knowledge to dance education.

In 1956, Martha Hill invited Sweigard to join the faculty of the Dance Division of the Juilliard School of Music. Sweigard developed a curriculum for the school that included an “Anatomy for Dancers” course and a “Posture Laboratory” for neuromuscular reeducation. Although Sweigard privately bemoaned the harmful effects the study of dance sometimes inflicted upon students, her work helped to bring Juilliard’s dance training practices into better accord with injury prevention principles. Hill described the influence of Sweigard’s teaching as follows:

More understanding of the instrument of the dance, the human body and the medium, movement; realistic self-evaluation by the student of his own potentials and limitations; greater freedom and skill in movement; increasingly fewer injuries; faster recovery from strains.

Juilliard’s preeminence as a collegiate dance program also provided Sweigard a platform from which to speak to the entire dance profession. She wrote articles on her approach in dance journals and spoke at several prestigious dance conferences. When the new field of dance science/medicine began to define itself during the 1960s, many connected Sweigard with the emerging discipline and considered her one of its pioneers.

Sweigard’s final scholarly achievement was developing a book presenting important facets of kinesiology, a discussion of the operation of the nervous system in the control of posture, and a description of her research and teaching practices. Human Movement Potential: Its Ideokinetic Facilitation also introduced the term “Ideokinesis” to describe a crucial feature of her educational approach. The word had been used in the writings of the pianist Luigi Bonpensiere to explain aspects of his piano pedagogy. Sweigard explained her interpretation of the term as follows:

Kinesis is motion, here defined as physical movement induced by stimulation of muscles…. Ideo, the idea, the sole stimulator in the process, is defined as the concept developed through empirical mental processes. The idea, the concept of movement is the voluntary act and the sole voluntary component of all movement. Any further voluntary control only interferes with the process of movement and inhibits rather than promotes efficient performance.

With the assistance of her husband, research biologist Fritz Popken, Sweigard completed Human Movement Potential while battling a major illness. She died at her home in Tompkins Cove, New York, just months before the book was published in 1974.

—Pamela Matt (Revised 2024)

Lulu Sweigard’s Human Movement Potential can be purchased through Amazon.

Bibliography for Lulu Sweigard

Brunnström, S. “The Changing Conception of Posture: Methods of Dealing with Faulty Posture,” The Physiotherapy Review 20 (2): 79-84, 1940. Traces concepts of proper posture originating with the “standing at attention” approach prescribed in Swedish Gymnastics; explains the biomechanical futility of common postural admonitions; gives high praise to Todd and Sweigard’s innovative teaching methods.

Kaempffert, W. “Body Mechanics,” In “Science in the News,” New York Times November 24, 1940, D5. Cites Sweigard’s doctoral study; explains how Sweigard’s approach differs from conventional physical education; uses behaviorist concepts to acquaint reader with automatic reflexes governing posture; discusses use of imagery and constructive rest.

Litvinoff, V. “Of Sweigard, Body Education and Kindred Things,” Dance Scope 10(1): 51-64, Fall/Winter 1975-76. Compares Sweigard’s approach to other somatic approaches and other forms of movement education; critical of Sweigard’s mechanistic references and focus on western theatrical dance.

Popken, F. E. “Efficiency in Movement Through Ideokinesis (The Sweigard Method).” In R.E. Priddle (Ed.), Dance Research Annual XI: Psychological Perspectives on Dance. New York, NY: Congress on Research in Dance. 1978, 41-46. Explains the need for Sweigard’s work; summarizes the results of her research studies; defines ideokinesis and describes her teaching practices.

Sweigard, L. “Body Mechanics and Posture in Modern Life.” In Symposium on Posture. Phi Delta Pi National Physical Education Fraternity for Women. 1938, 18-27. Sweigard’s non-traditional views on posture and posture education procedures are described; other authors also present conflicting views of posture and body mechanics.

———Bilateral Asymmetry in the Alignment of the Skeletal Framework of the Human Body. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis. New York University, School of Education, 1939. Sweigard’s analysis of bilateral deviations in postural alignment found in a study of nearly 500 subjects.

——— “The Athenia Disaster – My Story: An Eye Witness Account.” Alumnus – Iowa State Teacher’s College January 1940, 5-8. Sweigard describes her personal experience of the attack on the S.S. Athenia at the beginning of World War II; the story of her escape, rescue and care for the wounded passengers is accompanied by quotations from other passengers praising her heroism.

——— “Posture and Body Mechanics.” In Constance J. Foster (Ed.), The Attractive Child: The Care and Development of your Child’s Beauty. New York, NY: Julian Messner, Inc. 1941, 235-259. Sweigard describes the development of posture and proper care of the child’s body; suggests frequent periods of rest as an alternative to usual postural admonitions suggested by parents and teachers.

——— “Learning to Rest,” Self Magazine May 1946, 13-15. Introductory article on the importance of rest in improving posture; written for the layperson.

——— “Constructive Rest,” Self Magazine June 1946, 21-22. Presents a visualization of the body in the constructive rest position as a bag of sand with sand flowing in various directions to promote a more balanced musculoskeletal system.

——— “Postural Difficulties: Part One,” Self Magazine August 1946, 8-9. Short discussion of common postural problems.

——— “Postural Difficulties: Part Two,” Self Magazine September 1946, 25-27. Describes features of the lordotic posture; presents images for the pelvis, legs and feet.

——— “Psychomotor Function as Correlated with Body Mechanics and Posture,” Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences Ser. II, 2 (7): 243-248, May 1949. Reprinted in Nadel, M.H. and C. G. Nadel (Eds.), The Dance Experience: Readings in Dance Appreciation. New York, NY: Praeger Publishers. 1970, 358-365. Explains that attempting to change posture “at will” is not effective; asserts that posture can be “reconditioned” toward greater mechanical efficiency through mental activity; draws distinctions between muscular efficiency and relaxation.

——— “The Dancer’s Posture.” Impulse 1961. San Francisco, CA: Impulse Publications, Inc. 1961, 38-43. Correlates findings from her study of bilateral asymmetry to the dancer’s experience of differences in the mobility of the thigh joints and preference for a more stable standing leg; explains tests of spinal flexibility and four principles guiding procedures used in the posture laboratory.

——— “Better Dancing Through Better Body Balance,” Journal of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation. 36 (5): 22-23, 56, May 1965. To support her idea that the dancer’s posture largely determines success in performance, Sweigard explains the relationship between posture and flexibility; warns of the dangers associated with teaching turnout improperly.

——— “Preface.” In Mabel Todd’s The Thinking Body. Reprint. New York, NY: Dance Horizons, Inc. 1972, ix-xi. Sweigard explains her initial interest in Todd’s unorthodox approach and summarizes the results of her own research studies. http://www.dancehorizons.com

——— “The Use of Imagined Action in Teaching the Dance.” In Boorman, J., and D. Harris (Eds.), Dance: Verities, Values and Visions. A Collection of Papers Presented at the Binational Dance Conference. Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. June 1971. Vanier City, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Association for Health, Physical Education and Recreation. 1973, 21-25. Lists the postural faults often found in dancers; describes principles to be used in teaching “imagined action” to dancers in a class setting and possible responses to the teaching.

——— Human Movement Potential: Its Ideokinetic Facilitation. New York, NY: Dodd, Mead and Co. 1974. Sweigard’s classic text presents musculoskeletal anatomy and physiology, kinesiology, and her approach to improving posture and body mechanics; the term “ideokinesis” is introduced as a name for the approach. http://www.univpress.com

Unknown. “Sweigard System Corrects Posture by Rest,” Life Magazine January 6, 1941. Photomontage of Sweigard’s teaching and diagnostic procedures.

Williams, D. “Sweigard: A Memorial Tribute.” From a program for a SEHNAP faculty gathering at NYU, Fall 1980. Recounts Sweigard’s accomplishments; describes her pioneering work in movement education along with the obstacles she encountered in promoting her ideas and methods.

Williams, D. “On Human Movement Potential: A Review Article,” Journal for the Anthropological Study of Human Movement: Special Issue on Semasiology 1(4): 288-298, Autumn 1981. A tribute and remembrance of Sweigard; provides insights to those who would study her book from the linguistic, philosophical, psychological, medical, artistic, educational or anthropological points of view.

(c) 2023 thinkingbody.org. All rights reserved. Reprint with permission only.