Barbara Clark began lessons at Todd’s Boston studio with a strong personal interest in human movement. Born in Vermont in 1889, Barbara considered herself the weakest of the seven children in her family. She did not crawl as a baby, and then a childhood illness, later thought to be polio, hampered her confidence in movement. Since she was unable to keep up with her siblings in their work and play on the farm, the family limited Barbara to household chores and encouraged her scholarly interests.

After graduating from high school, Barbara reasoned that college studies focused on movement would help her to overcome her difficulties. She enrolled in the physical education program at Oberlin College but made very little progress despite her best efforts. The faculty advised Barbara to take up another major and limit her exercise to a daily walk. None of the other college subjects she tried captured her interest, so she returned to her family life in Vermont.

At the age of 30, Clark entered a two-year nurse’s training course at Faulkner Hospital in Boston. She liked the balance between the mental and physical work that nursing offered, although the required lifting of heavy patients often strained her back. To avoid recurring injuries, Clark focused on pediatrics and found great satisfaction in this aspect of nursing. Upon graduating from the Faulkner program, Clark established her professional reputation in Boston as a highly qualified “baby nurse.”

In 1923, Clark started private lessons at the Mabel Elsworth Todd Studio in Boston. After a few sessions, she was convinced that the lessons with Todd and her assistant teachers were lessening her back pain and visceroptosis. The assistant teachers were less enthusiastic, concerned that Clark was “so in need of help and it will take so long to get results that she won’t have the courage, patience and money to stay with us.” Far from being dissuaded, Clark relished every lesson, sensing the improvement in her posture and movement.

After several months of lessons and Todd’s informal program of teacher training, Clark began teaching the children who came to the studio. Todd welcomed this arrangement recognizing that most children would not be able to internalize the imagery she derived from anatomy and mechanics. Clark explored ideas for simplifying Todd’s material and making the lesson experience interesting for children. She often began by having the child feel a small, round, dampened sponge as an image of the relaxation desirable in the rib cage. She painted “sitting spots” on a small stool to facilitate the children’s awareness of the tuberosities of their ischia. Her recitation of stories and rhymes during the table work helped them to follow her tactile directions.

Clark also found ways to apply Todd’s ideas in her nursing practice. Some of the babies she worked with exhibited developmental delays and poor coordination. The sensory experience of her touch in the table work procedures helped them to improve. Clark also encouraged the practice of rolling, crawling and other developmental movements that built the child’s readiness for upright posture. In addition to the lessons she prepared for the children, Clark taught their parents strategies to encourage improved coordination between lessons.

In 1929, Clark published a small pamphlet entitled Structural Hygiene for the Preschool Child: Steps in the Baby’s Procedure for Balance and Movement. She distributed it in lectures for parent groups and women’s clubs throughout the city. Interested pediatricians kept copies in their offices.

Miss Clark also shared her knowledge of posture and developmental movement with the preschool teachers in training at the Ruggles Street Nursery School. Ruggles Street was the first teacher training program for preschool teachers in the United States. Clark worked there as the school nurse and regularly assessed each child’s physical development.

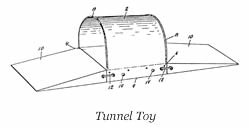

At Ruggles Street, Clark designed and modified play equipment to encourage optimum physical development for the children attending the school. Her best design was the Tunnel Toy, a small tunnel that youngsters could hide in, crawl through, or straddle. Delighted by the children’s enthusiastic use of the toy, Clark patented her invention, arranged for manufacturing, and sold it to nursery schools that were opening across the nation.

At Ruggles Street, Clark designed and modified play equipment to encourage optimum physical development for the children attending the school. Her best design was the Tunnel Toy, a small tunnel that youngsters could hide in, crawl through, or straddle. Delighted by the children’s enthusiastic use of the toy, Clark patented her invention, arranged for manufacturing, and sold it to nursery schools that were opening across the nation.

The success of her work with children inspired Clark to begin to devise a unique interpretation of her teacher’s educational method for older pupils as well. Clark wanted to create simple anatomical drawings that were easier for pupils to grasp than the detailed illustrations in anatomy books. As Todd diminished her presence in the east coast studios and began wintering in the west, Clark left Massachusetts to study drawing in New York City and develop her ideas for simple anatomical imagery. Ultimately, she planned to develop a series of “body alignment manuals,” written in a practical style that could assist everyone in their quest to become, as she put it, “physically educated.”

In New York, Clark met Dr. Lulu Sweigard, a physical education graduate of Teachers College who conducted a study that measured the results of Todd’s educational procedures. Sweigard was teaching her interpretation of Todd’s work in the physical education department of New York University. Clark observed Sweigard’s classes and briefly became her assistant. Clark also relieved Sweigard of an overload of private pupils, primarily from the performing arts.

Clark was particularly delighted to work with dancers, sensing their affinity for the approach to Todd’s work that she was developing. Eventually, Clark groomed a few of those students as teachers of her version of Todd’s approach, which she referred to as “Mind-Body Integration.” In the late 1950s, she prepared a two-year curriculum of group lessons for the actor André Bernard and the dancer Joanne Emmons to teach in New York City. She continued to mentor Bernard when he began teaching at the acting studio, Drama Tree.

In 1963, Clark self-published her first manual. Let’s Enjoy Sitting, Standing and Walking which focused on the balance of the axial skeleton. The imagery was to be pictured in simple daily activities, such as sitting down and standing up, walking, tying one’s shoes, and in the practice of the child’s developmental movements. Interested students spread the word about Clark’s manual, which she distributed by mail from her apartment.

Clark’s second manual, How to Live in Your Axis – Your Vertical Line (1968), was designed to supplement the classes taught by her student André Bernard, when he began teaching at Tisch School of the Arts. Clark’s drawings for this manual were more abstract, and the instructions assumed the readers were familiar with complex movement. This manual presented Clark’s imagery for the arms and shoulders and ideas for integrating movement with breathing. The centerpiece of the work was a visual image that captured one of Todd’s mechanical concepts — the balance of compression forces conveying weights “down the back” of the body, with tensile forces suspending weights “up the front.”

Clark’s second manual, How to Live in Your Axis – Your Vertical Line (1968), was designed to supplement the classes taught by her student André Bernard, when he began teaching at Tisch School of the Arts. Clark’s drawings for this manual were more abstract, and the instructions assumed the readers were familiar with complex movement. This manual presented Clark’s imagery for the arms and shoulders and ideas for integrating movement with breathing. The centerpiece of the work was a visual image that captured one of Todd’s mechanical concepts — the balance of compression forces conveying weights “down the back” of the body, with tensile forces suspending weights “up the front.”

By the late 1960s, Clark had attracted a new generation of students exploring “post-modern” dance. Her work enhanced their fascination with pedestrian movement and helped them to perfect its performance. Some of the dancers began infusing her imagery into their dance teaching. Although pleased, Clark was only remotely interested in the direction the dancers were taking with her work. Instead, her focus remained riveted on developing the drawings and lessons for her third manual. Mary Fulkerson, Marsha Paludan, Nancy Topf, Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen, and several Contact Improvisation performers had lessons with Clark during that period.

In the late 1960s, Clark became increasingly concerned about continuing to live in New York City, which was becoming very expensive and rather dangerous for senior citizens. Encouraged by several University of Illinois dance graduate students and Marsha Paludan, Clark left the city and settled in Champaign-Urbana. The dance students were eager to study with Miss Clark because of their interest in a new image-based dance technique that Paludan and Joan Skinner created at the university called “Releasing.”

With the help of John Rolland and Pamela Matt, Clark’s third manual, Body Proportion Needs Depth — Front to Back was published in Urbana in 1973. They continued to assist Miss Clark as she worked on her fourth manual. Matt’s graduate thesis became the first installment of her writing on Clark’s life and teaching. Clark’s fourth manual, The Body is Round – Use All the Radii was published posthumously.

Toward the end of her career, Clark had less energy for teaching and writing and became dedicated to using the “work” to conserve her vital energy. In that respect, she remained immersed in the experience of “Mind-Body Integration” until she died in 1982 at the age of ninety-three.

— Pamela Matt (Revised 2024)

A book that features Barbara Clark’s biography and writings is available at https://tbi-media.org.

Bibliography for Barbara Clark

Clark, B. Structural Hygiene for the Preschool Child: Steps in the Baby’s Procedure for Balance and Movement. Cambridge, MA: By the Author, 1929. A pamphlet for parents on the importance of developmental movement activities for infants and toddlers.

——– Let’s Enjoy Sitting –Standing–Walking. Port Washington, New York, NY: By the Author, 1963. Clark’s first body alignment manual devoted to improving posture and movement in ordinary daily activities.

——– How to Live in your Axis –Your Vertical Line. New York, NY: By the Author, 1968. Designed for dance students, with emphasis on imagery relating the movement of the arms and legs to the center of the body.

——– Body Proportion Needs Depth – Front to Back. Champaign, IL: By the Author, 1975. Emphasis on developing awareness of depth of the body to enhance postural balance.

Lichlyter, M.A. Following the Natural Pathway: Integrating Barbara Clark’s Somatic Principles with Modern Dance Technique. Unpublished Dissertation, Graduate School of Texas Woman’s University, Denton, Texas, 1999.

Matt, P. Mabel Elsworth Todd and Barbara Clark – Principles, Practices and the Import for Dance. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1973. Summarizes the early history of Todd and Clark’s contributions to the field of ideokinesis and suggests possibilities for using their work as an enhancement to dance training.

——— A Kinesthetic Legacy: The Life and Works of Barbara Clark (Revised Edition) Scottsdale, AZ: TBI Media, 2023. This biography of Barbara Clark also traces the development of Mabel Todd’s work and presents Clark’s out-of-print manuals and previously unpublished teaching guides. https://tbi-media.org.

Paludan, M. “Discovering Movement and Balance,” Contact Quarterly 9(2): 50-51, Spring/Summer 1984.

Paludan, M. “Developmental Movement by Barbara Clark,” Contact Quarterly 5(2): 39, Winter 1980.

(c) 2023 Ideokinesis.com. All rights reserved. Reprint with permission only.